In 1939 as part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, the USSR acquired further territories to the west of its September 1939 borders. Except in western Belarus, most people received Soviet power with at best reluctance and dread and often outright hostility. In the three Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania and western Ukraine there were active groups – from the OUN in western Ukraine and the former state apparatus in the Baltics – which stirred up Nationalist resistance to and subversion of Soviet power. These same forces were granted power and resources after June 1941 as they proactively collaborated with the Germans, receiving training and arms from them as they participated in local collaborationist administration and especially armed formations. The Soviets therefore confronted the problem of how, after June 1944 as they retook these territories from the Germans to resecure them in the face of nationalist insurgencies.

Alexander Statiev provides the answer. The Communists had experience in counterinsurgency practice from the Civil War. In the Civil War the Bolsheviks were very inexperienced but learned from their mistakes and had a set of policies that senior Party leaders – those who had survived Stalin’s Great Terror at least – had learned were effective. In the Civil War the Bolsheviks had used land reform and dividing the rural population as a means of creating winners and losers from their policies and so creating a support base, even if often narrow, for their actions among so called middle peasants and poor peasants. The Bolsheviks also had practiced brutality and ruthlessness not just against the insurgents but the civilian population but tempered it with mercy in not only offering but honouring amnesties to rebels against their rule who surrendered and were not leaders of a rebellion. The Bolsheviks practiced deportation of hostile populations outside of a rebellious zone to cut off any rebels from a support base that could provide them with food, intelligence and the possibility of blending in among seemingly passive civilians. Finally the Communists had learned that empowering some in rebellious regions to take responsibility for guarding their communities against rebels, under close Party supervision and leadership, could give many in rebellious communities a stake in the survival of the regime through their own actions in destroying members of their own community who went against the authorities.

Crucially, the Communists not only learned from and refined these policies after the end of the Civil War but added to them. Statiev also makes clear that the Communists as they pursued counterinsurgency were very much guided and indeed sometimes blinded by ideology. Confronting insurgency in the western lands of the Soviet Union the Soviets after 1944 were not cynical in insisting that the rebellion was powered by what they called Kulaks or rich peasants and ‘bourgeois nationalists’ – middle class professionals from before 1940 and small business owners who regarded themselves as representatives of the ‘true’ nation – to the contrary from Stalin downward this was a matter of belief in the Party. Such belief guided how the Communists would wage counterinsurgency. It allowed them to seize and exploit certain divisions and opportunities to defeat the insurgency but in other cases exacerbated the rebellion needlessly beyond where it need have gone had a different route been chosen. Despite these ideological blinders, the Communists succeeded in effectively extirpating every insurgency they confronted. And they did not do it through overwhelming firepower, terror and force. To the contrary, the practice of Soviet Communist, indeed Stalinist, counterinsurgency was less sanguinary than one might imagine if one were to rely on western histories often influenced by extremely biased and self-interested ‘bourgeois nationalists’ self-pitying narratives.

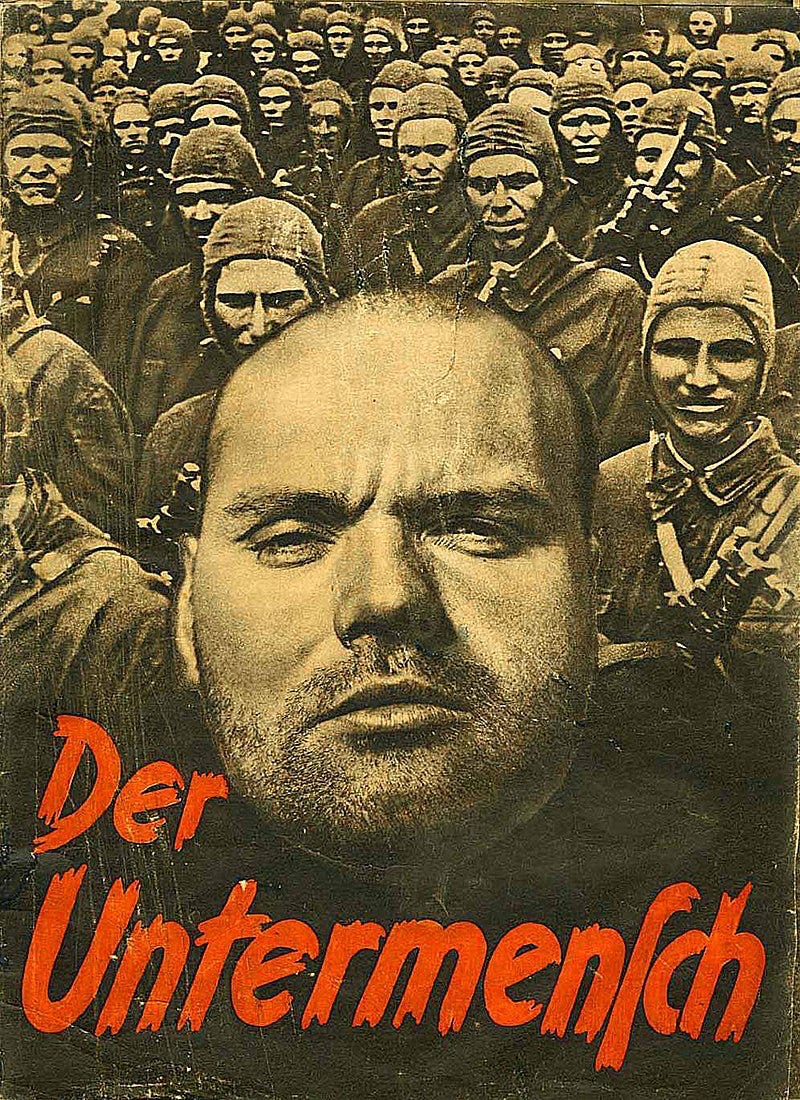

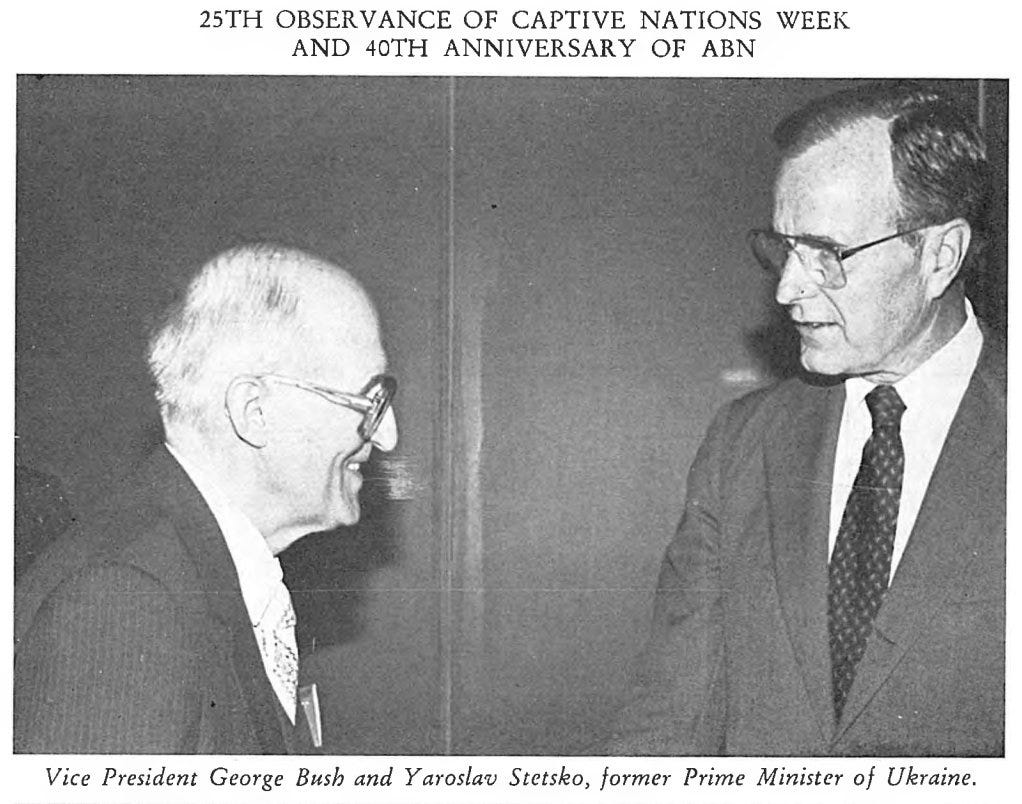

None of the insurgent groups the Communists confronted could meaningfully be described as politically democratic or liberal. To the contrary the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and the Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF) as well as the smaller groups in Latvia and Estonia all had their roots in armed formations that had been formed by collaborationist administrations from 1941-1943. The insurgents had not just benefited from German arms and German training, they shared Nazi ideology. The Estonian Omakaitse nationalist militia for example had summarily executed more people than the NKVD before the end of June 1941 and later participated in and often initiated wholesale massacres of Jews. Later, the Omakaitse were deployed to ‘anti-partisan’ actions through the Baltic republics, Belarus and into Russia itself in the Pskov oblast. These actions were often little more than murder expeditions as anyone in the zone of operations was considered an enemy and killed. Although Lithuania is the one Baltic country that did not create an SS unit, they scarcely needed to. In June and July 1941, 7,800 Jews were killed in the Kaunas region alone by the Lithuanians without any instigation from the Germans. 20 Lithuanian police battalions participated directly in the Holocaust and it was these men who – along with their compatriots – formed the core of the armed guerrillas who resisted returning Soviet power. The OUN – you can read about that in my review of Bandera.

The Guerrillas had a popular basis of support but they had a few weaknesses. Their hopes for ejecting Soviet power were on the basis of a new round of war between the Soviet Union and the western powers. More war was the last thing most people in the western lands of the Soviet Union wanted. This gave Soviet power one great advantage, people were exhausted and had seen a lot of blood and horror. Even though they did not trust and often feared and hated Soviet power, they were ready to submit so long as in return for their submission and lip service to Soviet power they were left in peace. The guerrillas, despite their sympathy for them, were denying them that peace. Second, the guerrillas were often arrogant and brutal. Anyone who took up positions of responsibility in the Soviet administration, whether school teacher, collective farm director, Komsomol youth organizer, was often a target and those people were not just killed but brutally murdered by the guerrillas. The UPA for example would murder entire families of ‘traitors’ including children. In one instance in June 1948 a horrified MVD patrol discovered a pile of human legs of people dismembered by the UPA as ‘traitors’ only a few of the dead could be identified. This brutality gave people reason to fear and hate the guerrillas and this in turn gave the Soviets openings.

The Soviets first broke down the initially very large and substantial armed formations they confronted. Second echelon Red Army units and NKVD security divisions combed the countryside and forests for large guerrilla formations and destroyed them. Often this was fairly easy as the guerrillas were initially – in all instances – confident of their superiority against the Soviets and so readily operated in large formations that were fairly easy to track, pin and destroy. Often, particularly in Ukraine, the guerrillas would attack Soviet formations themselves only to be utterly destroyed or suffer very heavy casualties. In all instances where the guerrillas attempted to set up urban cells, these were very quickly tracked and dismantled by the NKVD and later (after 1946) the MGB and MVD. In Lithuania’s case the urban cells were dismantled by early 1946 and while it took longer in Ukraine – it was only because of the persistence of attempts by OUN-UPA to establish cells that it took longer. Their effectiveness was always minimal.

Once the guerrillas recognized though that they stood no chance in open combat against either the Red Army or the NKVD they split into smaller, harder to track mobile units, or more often blended in among the local population and this is where the rest of Soviet tactics came into effect.

As the insurgencies were primarily rural based Soviet agricultural policy became particularly relevant to dividing rural communities and creating a group who supported Soviet power and a group which opposed it. Before collectivization the Soviets first redistributed land from large landowners, the Churches, and the class of wealthier peasants called Kulaks and distributed it to poorer peasants. The Kulaks often did not just have their land taken from them, they were officially harassed, shown no latitude or mercy for failing to fulfil delivery quotas to the state and were often immediately suspected of hiding guerrillas. This turned any potentially neutral Kulaks into either passive opponents of Soviet power, supporters of the guerrillas or even into guerrillas. Initially this fueled the insurgency and added to its manpower. It meant that the Soviet insistence they were fighting a Kulak and bourgeois nationalist set of guerrillas turned into a self-fulfilling prophecy but this also meant the other methods employed became – perversely after the security situation initially deteriorated – much more effective as the categories of the population the Soviets wanted to target were more or less the correct categories to target. Collectivization though mitigated against whatever advantages the Soviets gained from land redistribution. Even poorer peasants soon expected to lose their land to the moment when collectivization occurred. But even then collectivization created its own set of winners and losers both to continue dividing rural communities and to concentrate the rural population into larger but more easily observed and policed communities. Overall land reform and collectivization were less successful at defusing the source of the insurgency than in helping mould the insurgency into a more recognizably class based warfare and dividing rural communities enough that they were never able to fully unite against Soviet power.

The Soviets also formed so called ‘destruction battalions’ which were lightly armed formations that had the power to patrol near their own communities, to enforce certain aspects of the law and to protect their communities from guerrilla raids. The Soviets were aware that the majority ethnic groups were usually unreliable. As such minority ethnic groups and Party members often were very highly represented in these ‘destruction battalions.’ This meant that many of these battalions were made up of people who had the most to lose should the Soviet regime fail against the guerrillas. Still, it would be erroneous to say that ‘traitorous’ ethnic minorities and Communists destroyed the ‘good and patriotic’ guerrillas. Most members of the ‘destruction battalions’ were neither ethnic minorities nor Communists, but farmers – often poor or middle peasants from the majority ethnic group. Initially they were poorly trained. Some were easily defeated by the much better trained guerrillas. Some in western Ukraine defected to the guerrillas. But most were either effective and loyal or ineffective but loyal. Once the war ended and demobilized Red Army soldiers were incorporated, their effectiveness improved and the authorities were able to devote more time to training them, further improving their effectiveness. These ‘destruction battalions’ were the primary force after late 1945 which fought the guerrillas. The worker’s militia and MVD troops were spread too thin to engage regularly. The destruction battalions, knowing that there was no future for them if Soviet power should fail – and also wanting to ascend the Soviet hierarchy – fought with determination and often identified guerrilla agents and undercover guerrillas and either wound them up themselves or called in the MVD or MGB to begin an investigation liquidate the guerrillas. As the quality of the destruction battalions improved the guerrillas found themselves more and more isolated from the rural population and resources and so became more and more ragged and desperate – indeed more and more resembling the epithet the Soviets applied to them ‘Bandits.’

The Soviets did not use armed force alone to isolate the guerrillas from the local population. Deportations were a key instrument of Soviet policy. Statiev shows that far from being an indiscriminate tool of repression whereby ‘good’ ethnic majorities were ‘replaced’ with ‘foreign’ Russians, deportations were targeted on a class basis and a political basis. The families of guerrillas and guerrilla sympathizers were subject to deportation orders – usually deportation to a remote corner of the Soviet Union, and not always Siberia. In cases where entire communities had supported the guerrillas they would be split up and deported throughout the Soviet Union. The threat of being uprooted and deported was often enough to make people either urge their guerrilla relatives to surrender, to turn their guerrilla friends and family into the custody of the MVD and workers’ militia – or for guerrillas themselves to turn themselves in either to be with their families in deportation or in the hope they could spare their families from deportation. Where deportation actions were carried out this cut off guerrillas from sympathy, support and resources and further strangled them and their recruiting base leaving more and more a population that was hostile – and one which benefited from moving into the houses and using the land of the deportees. For the deportess themselves while some never gave up their cause, others found the experience of deportation both demoralising but also the fact that the local on their arrival often viewed them with suspicion if not complete disdain as further social isolating factor to reinforce the idea that resisting Soviet power was futile, dangerous and they were an isolated, irrelevant and truly despised minority.

Deportations were effective because Soviet policy was tempered with mercy. The Stalinist regime, which had a deserved reputation for brutality and promising those who confessed to crimes mercy only to betray them and murder them was much less murderous and treacherous than it had been in the 1930s. As in the Civil War, guerrillas who surrendered during an amnesty were not only allowed to surrender, they were often – depending on their rank – let go free with the promise not to aid the guerrillas, albeit they would be subject to much closer workers’ militia and MVD supervision. If the guerrilla who surrendered was middle ranking they would be expected to perform acts which demonstrated their loyalty to Soviet power and burned their bridges definitively by turning in – or indeed turning on their former comrades. Some guerrillas who came in during amnesties became members of destruction battalions and brought their knowledge of guerrilla operating procedures to assisting the destruction battalion militia in detecting and defeating guerrillas. Others became commandos or operatives for the MGB or MVD which went hunting for guerrilla units and fought them. Once these former guerrillas had done this though, they were free and, having turned themselves in, their families and friends were spared deportation. This honouring of amnesties made the prospect of surrender very tempting for many guerrillas. It is why the SB of the UPA punished those who spoke of surrender or who had surrendered not just with execution but very brutal and often sadistic executions to keep guerrillas fighting to the bitte end. The contrast between Soviet mercy and guerrilla brutality though encouraged more to accept offers of amnesty and turn on their former comrades to get back to living a normal life.

Still there was work to be done in the midst of all this by the MVD. The NKVD (and after March 1946 the MVD) and MGB were always the primary all-Union power organs devoted to extirpating insurgency. In contrast to western practices – the trouble zones were not flooded with MVD and MGB personnel. To the contrary, despite being slightly reinforced, the MVD and MGB were stretched thin and expected to make due with what they had. For the MVD this meant only 34,000 men were devoted to western Ukraine. This notwithstanding both security organs made excellent use of what they had. In addition to setting up networks of agents in the villages, providing mobile motorised patrols to quickly close in on large groups of guerrillas the MVD and MGB both set about penetrating the guerrillas with agents and tearing them apart from within. As mentioned, amnestied mid-ranking guerrillas or guerrillas who were members of the SB often had to undertake dangerous work on behalf of Soviet power to earn their pardon. This meant often they returned to their guerrilla units after the MVD concocted an escape that seemed violent but in fact was not. This did not always work. Mistrustful guerrillas would often kill the returnee outright or the amnestied guerrilla would betray his word to Soviet power. Most often though it did and the MVD and MGB gained valuable information about the guerrillas. These agents helped the Soviets pull the guerrillas apart from the inside. The MVD and MGB also often devised ingenious schemes to get the guerrillas to reveal themselves and mind up huge segments of the guerrilla network in one swoop. The results were that the guerrillas save a brief period in early 1946 and only in western Ukraine constantly found themselves on the backfoot against the security forces. The paranoia the effectiveness of the MVD and MGB induced also further heightened mistrust and hysteria in guerrilla ranks, making offers of amnesty from the Soviet authorities all the more tempting.

Finally, the Soviets, unlike during the Civil War, used the Churches as active instruments of policy. Though official harassment did not end, Stalin was both impressed by and grateful to the Russian Orthodox Church for giving his government support during the Great Patriotic War. In return Stalin restored some of the buildings and lands to the Church and even allowed the reopening of some seminaries and reduced harassment against believers. The Orthodox Church in turn assisted in the borderlands by moving against rivals and helping wind up the Greek Catholic Church and absorbing its buildings and properties as well as bringing Ukrainian Orthodox dioceses and bishoprics more firmly under the control of the Moscow Patriarchate. The Church preached in favour of Soviet power and against the guerrillas, denouncing their actions as sinful, un-Christian, and futile. This shook many in the still faithful peasant communities and even guerrillas and helped weaken morale while also demonstrating that Soviet power had moderated somewhat compared to its earlier days. In the Baltics where the Catholic and Protestant religions were more dominant, the churches were less willing to subordinate themselves and consequently Soviet policy was far more anti-clerical.

Overall, what are we to make of it? Statiev does not shy away from detailing Soviet brutality and Soviet crimes, but he points out they were exceptional, not the norm, and very often punished with demotions, firings or even prison sentences for the guilty. Depending on the severity of the crime, some abuses of power were punished with execution. Still others were not and were protected and this undermined Soviet power and the counterinsurgency strategy but never so severely as to appreciably increase support for the guerrillas. Even more astonishing, to me at least, Statiev concludes that Soviet counterinsurgency was lower key, lower cost, less firepower intensive and far less brutal overall than the counterinsurgencies of not just Western backed authoritarian regimes (think Guatemala) but also Western democratic regimes who have used heavy firepower, deportations, torture, death squads in their own counterinsurgency efforts. Soviet counterinsurgency had its problems and imperfections. In part Marxism-Leninism strengthened counterinsurgency conceptions and practices but in other ways constrained it. Nevertheless, it was effective. The Soviets won. OUN-UPA, and the remnants of the armed collaborationists in the Baltics were defeated and the areas won for Soviet power.

So then, I highly recommend this book. In addition to be highly readable, the product of a near decade of indefatigable research, it dispels a lot of myths about the practices of the Stalinist regime, highlights that a lot of the horror stories of brutality and mass death are mistaken or exaggerated. It gives a more complete picture of an often ill studied and unknown aspect of WWII and Soviet history. It also shows that in the past, against ruthless, trained and committed enemies, the good guys won. They can win again.

Donbass Devushkha is an independent channel and we want to keep it that way to ensure we can produce more and higher quality content for you and you alone. If you would like to support us please consider visiting our online store or donate via DD Donation. If you prefer to use crytocurrency please use the link provided below:

BTC: bc1qpf8gzgqtcr8vs9usemjan96uu944uy0ccc608e

ETH: 0x687943EC52741C1dcb0e24D7668F9aE8596581BB