In 2014, just before the Maidan Revolution and coup shook the world Polish-German historian Grzegorz Rossolinski-Liebe published an extraordinary book. This book is vital for anyone who wants to understand Bandera, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), Ukrainian Nationalism and why, rather than being a fringe phenomenon Bandera and his organization were mainstreamed after 1991 in Ukraine by its ‘pro-European’ politicians.

Although Bandera is on the cover and the book does cover his biography the focus of the book is less on Bandera’s life than Bandera the phenomenon. He is the central character of the book, but it is not – so to speak – history from his first-person perspective. Indeed, the biography of Bandera is the central focus of only three chapters. The rest are dedicated to the OUN and the Bandera cult, not Bandera the man.

Rossolinski-Liebe makes this clear by situating the social and political milieu Bandera would move in as the focus of the first chapter – before he gives any information about Bandera’s biography. Ukrainian nationalism was, from its birth, a far-right nationalism. In part this was because Ukrainians found themselves in two separate empires, the Habsburg and Russian Empires. The only way Ukraine could be made as a state and to some extent a people was by rending apart two powerful empires and forcing Ukrainians to shed their imperial identities and have only Ukrainian ones.

Ukrainian nationalist intellectuals, such as Mykhailo Hrushevs’kyi invented a glorious past to try and put Ukrainians on the same plane as other ‘Great Peoples’ in Europe. Others such as Mykola Mikhnovs’kyi – ironically an eastern Ukrainian – went further though and quickly took Ukrainian nationalism in a racist direction. It was Mikhnovs’kyi who demanded a Ukraine exclusively for ethnic Ukrainians – Jews, Russians, Poles, Hungarians, Tatars and others were to be expelled – and demanded a ‘greater Ukraine’ that would have extended from the Carpathians to the Caucasus. He also wrote the decalogue of the Ukrainian nationalist which stated among other things ‘do not marry aa foreign woman because your children will be your enemies…’ Mikhnovs’kyi in turn strongly influenced Dmytro Dontsov who “encouraged the younger generation to reject ‘common ethics’ and to embrace fanaticism because, as he claimed, only fanaticism could change history and enable the Ukrainians to establish a state.” The OUN accordingly, like Dontsov himself embraced far-right, ethnonationalist and fascist ideas. Indeed, Dontsov copied and mixed together many of his ideas from far-right German and Italian Fascist figures.

Another major influence on Bandera was the failure of the Ukrainian states that tried to emerge from late 1917 onward. All of them, two of which his father was involved in, failed utterly and were crushed by outside forces, either the Poles or the Bolshevik Reds – and often with a mix of assistance from the Germans and the White Russian movement. These same states were chaotic, unable to establish themselves, and their troops, especially from Symon Petliura’s committed murderous crimes against non-ethnic Ukrainians – particularly Jews. It was this milieu that Bandera grew up in and moved in.

Bandera himself did not have a particularly noteworthy life in many respects. One of eight children to Andriy Bandera, a priest in the Ukrainian Uniate Church (part of the Catholic Church but with Orthodox rites), Bandera’s brothers all died during the war – some in German concentration camps in murky circumstances but which were not due to being murdered by the guards or conscious ill treatment – and his sisters all survived the men of the family. He was a sickly child but tried to excel at athletics joining the Scouts-like organization Plast’. His entire family was dedicated to Ukrainian nationalism, but Stepan stood out for his single minded dedication to this. He was noted to be a charismatic speaker and had a commanding presence when he spoke – despite being a relatively diminutive and thin 5’3 man.

In 1932 Bandera, still only 23 took control of the Homeland executive of the OUN. Within two years, using money provided by the government of Lithuania, he had orchestrated a terrorist campaign that culminated in the assassination of the Polish Interior Minister Pieracki in June 1934. Shortly before the assassination Bandera was arrested and subsequently put on trial. However, this trial was the beginning of the Bandera myth. At the trial Bandera refused to answer the prosecution in Polish – even though he spoke Polish fluently – and answered only in Ukrainian. He and the 12 other OUN defendants were rude and contemptuous of the court’s authority – but this was reported on rapturously in the Ukrainian language press. It was also the venue where the OUN premiered its new rallying cry and salute. As Bandera and other defendants were sometimes led away, they would shout “Slava Ukraini! [Glory to Ukraine!]” raising their right arms upwards and outwards just above the peak of the head in a fascist salute with shouted reply “Heroyam Slava! [Glory to the Heroes!]” The cry of Slava Ukraini, Heroyam Slava, often now said proudly and with a smile by western politicians was born as a fascist cry – a Ukrainian Saluto al Duce! Or a Sieg Heil!

In the court in Lvov in 1935, where Bandera was tried again, he had greater opportunity to expound in Ukrainian on his ideals – and it includes this quote which gives an idea of what Bandera, by then only 26 and his supporters were striving for and the words which fired the imagination even then of hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians. “The measure of our idea is not that we were prepared to sacrifice our lives, but that we were prepared to sacrifice the lives of others.” This was a renunciation of the normal moral universe where the supreme ethic – dictated for a long time by the Christian example – was willingness to sacrifice oneself in defence of others. Bandera inverted it where the sacrifice of others for one’s goals was the supreme ethic. Despite being a lifelong Christian and religiously observant Bandera often said, “the nation before God.”

Immorality and amorality are exactly what the OUN proceeded to do after 1939. Already in September 1939 Bandera had broken out of jail and in the chaos of the German and then Soviet invasion the OUN made an attempt to construct its ethnostate killing 3,000 Poles and an unknown number of Jews in western Ukraine in September 1939 before being chased out. Bandera and the OUN watched German actions against the Poles and Jews in Poland and instead of being uneasy were excited. They would use those methods against those they saw as their enemies.

Bandera engineered a split in the OUN between the much larger OUN (B) led by himself and the OUN (M) led by Andriy Melynyk. In part the split reflected generational differences. But the differences were over power, control of the organization, and the expediency of certain means. Both were racist, authoritarian, and fascist.

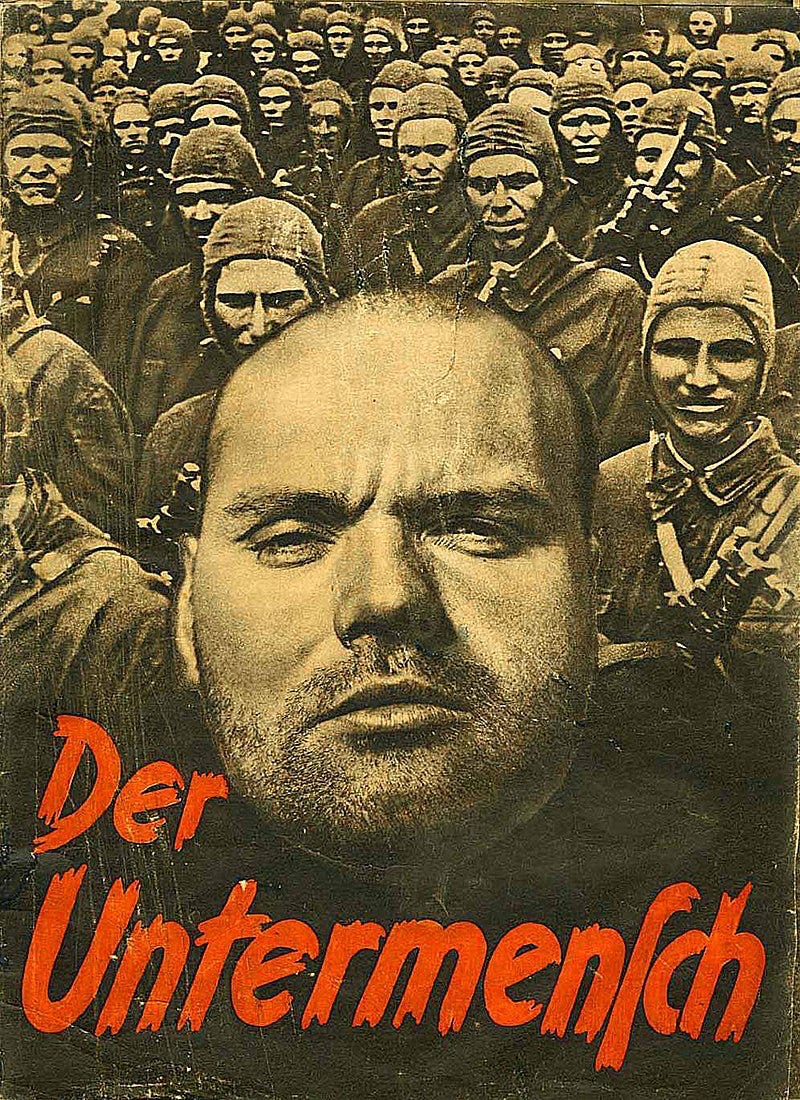

Bandera organized the second OUN congress in Krakow from 31 March 1941 to 3 April 1941. At this Congress Bandera laid out his vision for Ukraine. It was a vision of violence and – for all who did not agree with the OUN’s vision for Ukraine – hopelessness. All political life was to be subsumed in the OUN which would be the only political party allowed in Ukraine. The Jews were to be exterminated. Any non-Ukrainian ethnic groups were to leave Ukrainian territory immediately or be killed. Any ethnic Ukrainians who disagreed with the OUN politically were to be killed. Even before the German invasion the OUN were to go ahead of the invading German troops and start insurrections. Before the Germans arrived the OUN were to have established themselves in the local administrations and found the Ukrainian state and then immediately proceed out to mobilize military age men for military training to go and conquer the greater Ukraine of Mikhnovs’kyi. All Ukrainians were to be required to swear an oath of allegiance to Stepan Bandera as the providnyk and the OUN as the sole ruling party of Ukraine. Finally, this congress established the Red over Black flag you often see in Ukraine today as the OUN’s flag. It’s meaning: blood and soil.

German military intelligence trained OUN-B members in basic military tactics so they could start the planned insurrections and with assistance from the SS organized 700 OUN-B members into two SS battalions made up of Ukrainians and partially officered by Ukrainians – Roland and Nachtingall, including Roman Shukhevych. The OUN-B were not exactly competent. Some groups were intercepted and killed by the NKVD as they tried to cross the Soviet border. In other instances, they started premature uprisings which were put down by the NKVD.

As such the OUN-B had lost a lot of the members who were supposed to establish a Ukrainian state ahead of the Germans. Without permission from Hitler Yaroslav Stets’ko proclaimed a Ukrainian state over the radio in Lvov on 30 June 1941. Interestingly, their role model for this was the declaration of the Croatian state by Ante Pavelic and the Croatian fascist Ustaše earlier in the year.

The OUN further proceeded to imitate the Ustaše by launching a horrifying pogrom against Lvov’s Jews on 1 July 1941 in a spectacle that left even a number of Germans queasy. Rossolinski-Liebe holds nothing back on this. Despite spontaneously enacting part of the Final Solution for the Germans, Hitler was displeased with the OUN’s declaration of Ukrainian statehood. Such an outcome did not correspond to his plans for Ukraine. Bandera was arrested and put in concentration camp but put in ‘honorary custody’ which is to say he was given a heated cell, adequate bedding, and three solid square meals a day, he was allowed books and writing material. In other words, he was treated far better than most ordinary prisoners were in the Third Reich to say nothing of Concentration Camp inmates. Bandera as such was never in Ukraine during WWII.

Meanwhile the Germans wound up the OUN-B when they collaborated but refused complete subordination and continuously murdered OUN-M activists. Nevertheless, OUN-B activists remained at all levels of Ukrainian administration under the German occupation and used their positions to target their enemies when German policy was to target these same groups including Russians and Jews. OUN-B members were also disproportionately represented in the Ukrainian police who guarded sites where Red Army prisoners were worked to death, assisted in deportation, and shooting actions in the Holocaust, and sometimes participated in anti-partisan operations that were usually more akin to organized massacres of civilians rather than military operations as such.

As the tide of the war began to turn the OUN-B decided to jettison collaboration with Germany. Under instructions and orders the OUN-B members in the administration and especially the police deserted their posts and fled to the forests or blended in among the population. This did not signal the start of anti-German warfare. Led in Ukraine by Roman Shukhevych, the OUN-B showed benevolent neutrality to the Germans and instead now as so-called Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) the OUN proceeded to commit genocide against the Poles of western Ukraine. To save ammunition this often involved turning ethnic Ukrainians against their Polish neighbours and bludgeoning people to death.

Rossolinski-Liebe also exposes the myths about the UPA being a pan-Ukrainian force composed not just of western Ukrainians and fascists, but democrats, eastern Ukrainians, and even Jews. Rossolinski-Liebe proves this is demonstrably false. The overwhelming weight of testimony from UPA insurgents, UPA documents and Jewish survivors is that such Jews as there were in the UPA were people captured from ‘forest bunkers’ and were only spared if they had skills useful to the UPA such as a tailor, blacksmith, doctor, or nurse. Any Jews who were not useful were bludgeoned to death. Those Jews who were useful were often physically abused or murdered at will for fun, and whenever a Red partisan or Red Army formation got to close – the Jews with the UPA would all be murdered. As for eastern Ukrainians there were few of them, complained they were given the worst assignments, were never promoted, and sometimes in fits of paranoia were murdered by the OUN’s version of the SS the Sluzhba Bezpeki (SB). Attentive readers might note this is nearly the same as the SBU – modern Ukraine’s secret police.

Where was Bandera? In September 1944 he was released by the Nazis to reorganize the OUN. Bandera realizing which way the wind was blowing made himself scarce. But by the end of summer 1945 was already receiving help from Western Intelligence – the British and the Americans. There was another split in the OUN, Bandera’s group became the OUN Abroad (ZCh OUN). A putatively more moderate faction emerged around the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council (UHVR) which was made up of OUN members who shared Bandera’s ideology but did not regard him as the Providnyk and learned to speak the language of democracy and freedom while never renouncing or denouncing their fascist past. Bandera however could never be so subtle and while never proclaiming himself publicly to be a fascist spoke admiring of surviving fascist leaders and proto-fascist thinkers. Subsidized by both the US and UK Bandera lived much better than most displaced Ukrainians or indeed most Germans in Munich. The Zch OUN and UHVR competed for funds and attention and a claim to represent the UPA – with Bandera’s insistence on absolute subordination to his leadership alienating the surviving UPA members who were being systematically found, captured, turned, or killed by the NKVD and MGB. Bandera also used his funds to set up not just a printing press, but to disseminate propaganda and organize the Ukrainian diaspora in Germany around the far-right – and himself of course – but to also found a section of the SB which engaged in murder hunts with the Zch OUN and against the UHVR for anyone who went against Bandera or was suspected of being a Soviet agent. When UK and US intelligence tired of Bandera’s whims, he was safeguarded by West German intelligence, headed by the former head of Freemde Heere Ost Reinhard Gehlen – so another man deeply complicit in atrocities in the Soviet Union.

Bandera’s personal life continued in a state of being constantly engaged politically, writing, keeping fit and depending on who you ask displaying good humour and having a happy family life or being a man who beat his wife and raped a colleague’s wife and even raped his children’s au pair. This ‘heroic’ life was cut short by a former OUN member who had been turned by the KGB.

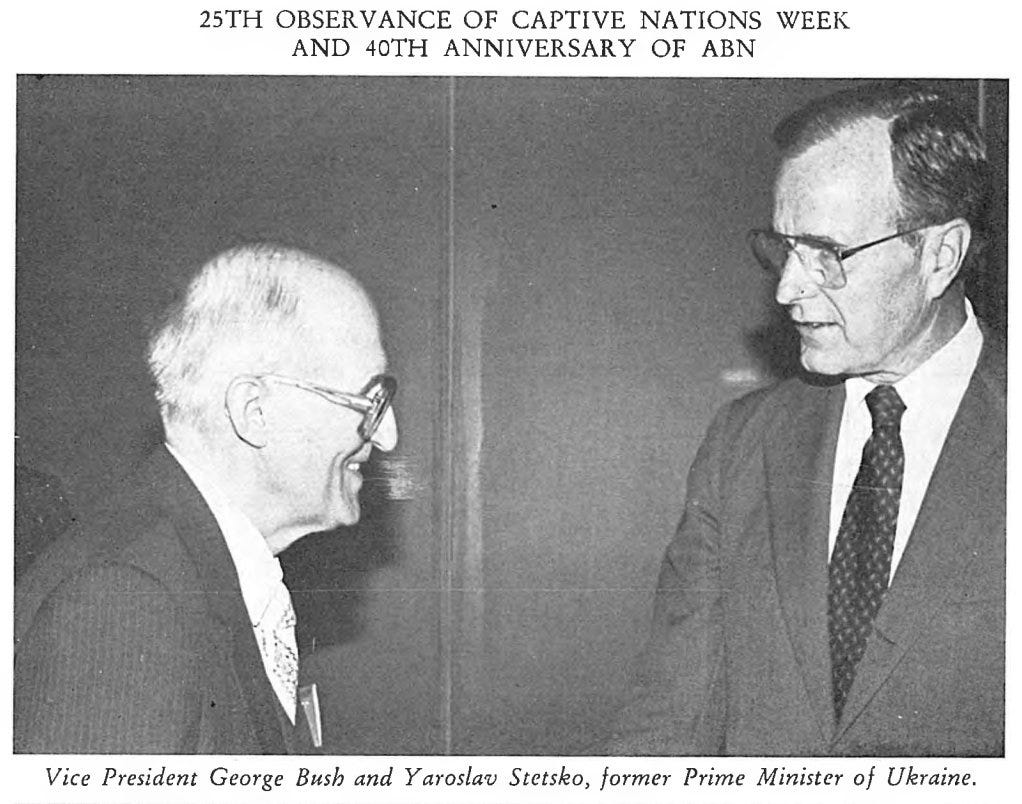

Bandera’s death gave birth to his afterlife. Despite the fractures he had caused in the Ukrainian diaspora he was immediately mourned and revered as the Providnyk. The anniversary of his death became a commemorative occasion for memory for the Ukrainian diaspora and every five or ten years an excuse to commit an outrage against a Soviet diplomatic mission. With time Bandera’s associations with genocide were able to be so diluted that Yaroslav Stets’ko, the man who had organized the Lvov pogrom was invited to speak to the US Congress and meet US President Ronald Reagan. Bandera’s son also denied any atrocities his father had committed and his grandson Stephen Bandera – named for his grandfather, continues to do so. Perversely while Soviet attempts to portray Bandera gave many an image of Bandera they could despise and vow never to arise again, it reminded people in western Ukraine as the years went by less of atrocities that had been committed – often against them – and more of Soviet excesses committed against them. The negative myth around Bandera came to be positively embraced.

This meant that when Ukraine emerged as a country after the fall of the USSR, the soil of Ukraine was a breeding ground for Banderism. In the West monuments and museums to him quickly sprouted up. Lvov Autonomous National University became the academic standard bearer in Ukraine for historical revisionism and a new orthodoxy which denied the role of the OUN in the Holocaust. Bandera was celebrated officially in film, television and eventually in 2008 by being made a Hero of Ukraine by pro-EU President Viktor Yuschenko. Only then was there a pushback from historians – primarily from the West – against the celebration of Bandera and from parts of Ukrainian civil society. By then though the stage had been set. Bandera had been normalized and was celebrated by much of the population.

That in effect works as a summary, what about as a book? The book is very well structured and written. After the introductory chapter on Bandera’s intellectual and political milieu it covers his life, the OUN and his afterlife chronologically. The book stands out – in my view – as a masterpiece of scholarship. Rossolinski-Liebe uses Polish, Ukrainian, Russian, German, and English language sources and a variety of those at that. In addition to numerous published works, it is evident that he indeed spent more than a decade researching the book to critically analyse and compare what was said by one source against what another said, and it shows in his writing and his footnotes. Given that Rossolinski-Liebe had to obtain access to primary source materials from both the secretive and often mistrustful of outsiders, remnants of the OUN as well as get past the hostile archival gatekeepers of the SBU what he was able to discover and unearth produces the most comprehensive study of Bandera and the OUN that exists in English. Rossolinski-Liebe also takes the time to debunk several myths created by Bandera, about Bandera and the OUN. He also painstakingly details how the OUN came to be, its origins, how Bandera came to prominence and later why he was protected after 1945. Even the briefest section, the afterlife of Bandera, his cult and how it came to take root in Ukraine is not lacking. Rossolinski-Liebe even managed to find a secret Bandera Museum in London – albeit it now appears that the museum is far less secretive since 2014.

It is weighty book, and it is a very recommended buy. The war in Ukraine is shaping our world and reshaping it. To a large extent modern Ukraine, the state and its people see Bandera and his movement as role models to be emulated and looked up to. If you want to know what and who it is that they revere, and that what Western politicians are implicitly endorsing when they cheerfully say “Slava Ukraini! Geroyam Slava” and why you are feeling the pinch every time you buy gas or go to the grocery store – this book will tell you the why of all that. To understand the world around you, to know it, can give you a sureness of mind, purpose and understanding that will allow to anticipate and withstand many challenges. For that reason alone, not just because it is a well written, and extraordinarily well researched book it is well worth the price to know why we are all being asked to pay the price for the dreams of Bandera.

Donbass Devushkha is an independent channel and we want to keep it that way to ensure we can produce more and higher quality content for you and you alone. If you would like to support us please consider visiting our online store or donate via DD Donation. If you prefer to use crytocurrency please use the link provided below:

BTC: bc1qpf8gzgqtcr8vs9usemjan96uu944uy0ccc608e

ETH: 0x687943EC52741C1dcb0e24D7668F9aE8596581BB